Journal Volume 4 2004

The County Wicklow Military Road

By Pat Power

Background

Many features have helped delineate County Wicklow's status among the counties of Ireland as the "Garden of Ireland". Its half million acres are blessed with an immensely varied landscape and superb coastline. Within the county the hand of man and the works of nature have complimented one another repeatedly. Examples shine out like Powerscourt, Mount Usher, Glendalough, Killruddery and a hundred other locations. Some places of unsurpassed beauty as the Valley of Luggalaw, Lough Dan, the two Lough Brays or the remote vistas of the Wicklow highlands might never have been seen by the general public but for an exceptional and original work of man, the 46 mile long “Great Military Road”, constructed between 1801 and 1809. This road, built for motives far removed from its present function as a leisure artery of the county, is Ireland’s only purpose built military road of any substance. With its surviving barrack buildings and generally unaltered structural state, the route is a historical monument of the first importance, but it also serves as the county's most utilised roadway in communication throughout Wicklow's outstanding mountain terrain, a unique duality. This is a remarkable feature for a historical monument, shared by few other major heritage sites in Ireland, with the exception perhaps of Dun Laoghaire pier.

The concept for a military road across Wicklow was not new even as the 1798 Rebellion swept over Wexford and Wicklow 200 years ago. In the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558 - 1603) and even earlier, when the Henrician Tudor administration was ruthlessly crushing the native Wicklow septs of the O'Byrnes and O'Tooles, it was discussed by various Lord Lieutenants and their Anglo-Irish warlords to construct an access into the Wicklow heartlands all the better to control the wilder and more remote places of the mountain lands. They never embarked on a full scale road as such, but portions of the landscape were modified to the military needs of the day.

Thus a short stretch of roadway was cut through the Glen of the Downs by order of Lord Deputy Grey in 1552. The “DeputiesPass” near Glenealy was another cutting made for military purposes when the Lord Deputy Russell had it cut in 1594 to supply his new military fortress in Rathdrum, founded as a settlement for English tenants, but now a fully garrisoned military camp.

Other large scale military building projects never came to fruition, although they were planned on paper like the grandiose “Osborne's Fort”, a great maritime citadel destined perhaps for to stand on Wicklow Head, but which was never even started. In the early 17th century and during the Cromwellian and Williamite wars, many military type structures were built such as earth walled enclosures, embankments and causeways across wet ground, some of which have lasted into modern times. Other military features shared dual purpose with civilian usage like “DunganstownCastle” (it was actually a fortified house) and “Cavanaghs Camp” in Glen Imaal. Military features are also recalled in place names such as “King Williams's Road” near Arklow and the “Williamite Camp” near Ballyrichard.

Other large scale military building projects never came to fruition, although they were planned on paper like the grandiose “Osborne's Fort”, a great maritime citadel destined perhaps for to stand on Wicklow Head, but which was never even started. In the early 17th century and during the Cromwellian and Williamite wars, many military type structures were built such as earth walled enclosures, embankments and causeways across wet ground, some of which have lasted into modern times. Other military features shared dual purpose with civilian usage like “DunganstownCastle” (it was actually a fortified house) and “Cavanaghs Camp” in Glen Imaal. Military features are also recalled in place names such as “King Williams's Road” near Arklow and the “Williamite Camp” near Ballyrichard.

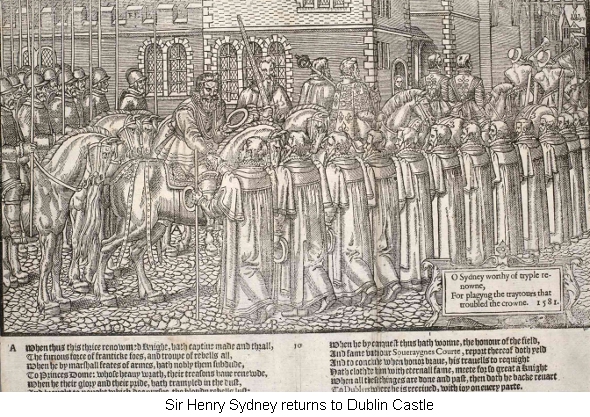

An old epigraph of the Dublin Pale summed up the fears and anxieties of its inhabitants towards the native Irish neighbours of the remote mountain lands in “O'Byrnes Countree”, ever visible from the city. In John Derrick’s “Image of Irelande” (1581) a short poetic caption of one of its woodcuts concludes:

“O Sydney worthy of tryple renowne,

For Plagyug the traytours that troubled the crowne. 1581”.

It was this last line which articulated the strategic worry perpetually debated by authority that something must be done with “Wild Wicklow” to make it less a haven to rebels, real and imagined. Nothing was done however and the issue was allowed to sleep. Yet the concept of securing the capital was not forgotten even as it slept and occasionally events would occur which would awaken the debate to secure Dublin from inaccessible Wicklow.

Despite the narrow Ascendancy politics of the 18th century, the social deprivation of its general population, and layer upon layer of uncivil Penal Laws the bulk of that century was one of relative stability and peace for County Wicklow. At times there were various scares for the government and local authority, like rumoured landings by the various Stewart pretenders, or reports of French recruiting agents infesting the countryside. Reactions to Europe's shifting politics were always likely to make authority run scared and such occasions sent the jitters through the military. On several such crises in far flung Europe, the county's armed forces were mustered for duty. No full scale war preparations were ever made however until 1780 when the perceived invasion from the army of revolutionary France became a real possibility.