Journal Volume 6 2010

‘Wild, Ideal, Romantic and Absurd’: Lady Arbella Denny and the Establishment of Dublin’s First Magdalen Asylum (continued/2)

Support, Management and Operation

In soliciting support for the scheme, appeal was made to the self-interest as well as to the piety and humanity of the public. Assistance was sought from all those ‘inspired with a truly Christian zeal to turn many to righteousness’, and readers were asked to pity the ‘diseases, poverty and brutal insults’ to which prostitutes were routinely subject. But, they were reminded, the evil effects of such practices were not confined to the woman herself. They extended to the wider community, breaching even the sanctity of the family circle, blasting ‘the bloom and innocence of youth of all ranks’, corrupting husbands, and through them passing on ‘distempers to virtuous wives and children unborn’.9

Such an argument seems perfectly designed to enlist women’s support for the new charity, as does the special appeal made to:

‘The ladies of this kingdom … who, with compassion equal to their own superior virtue, will certainly patronize an undertaking designed to restore many fallen and unhappy person of their sex to chastity, decency and competence.’10

Certainly, the Magdalen Asylum was novel in being almost entirely a female-run institution, at a time when women who involved themselves in charitable action almost invariably did so under the auspices of male-run organizations. Lady Arbella herself took charge of the day-to-day management of the House, and was closely associated with the charity from its opening until her retirement in 1790, when she was succeeded by her deputy, Mrs Usher. She was supported by a committee of fifteen ‘governesses’, elected from the lady subscribers, who visited the House regularly, adjudicated on matters of discipline, instructed the magdalens in various skills, and helped them to find employment on departure.11 In addition, female supporters provided financial and practical assistance: early benefactors included Mrs Edward Denny, Mrs Delany, the Countess of Louth and, in 1791, an anonymous lady who personally delivered £800 in banknotes to the House. Women also featured prominently among the donors to the collections at the adjoining Magdalen Chapel, which provided a significant proportion of the charity’s annual income. The chapel became one of the capital’s most fashionable places of worship, attracting congregations composed of ‘persons of the very first station, rank, character and fortune’, each of whom paid an admission fee of one shilling for the morning and sixpence for the evening service. In addition, annual charity sermons raised substantial sums: the largest collection, in 1792, raised over £300 - probably in tribute to the memory of Lady Arbella, whose death had occurred just two weeks earlier.12

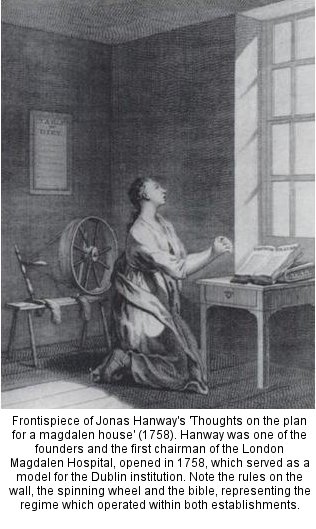

The Rules of Management, drawn up by Lady Arbella on the opening of the House, offer an insight into the principles upon which the charity operated. Designed to promote regularity and discipline in every aspect of the women’s existence, the regulations dictated times of rising (six o’clock in summer and seven in winter) and retiring (ten o’clock) and allocated set periods for ‘private devotions’ and meditation, prayers in the chapel and household chores. Even the duration of meals was to be determined by an hourglass placed in the centre of the table, an hour being allowed for dinner and half an hour each for breakfast and supper.13

Despite the acknowledgement by the charity’s founders that punishment alone was an ineffective approach, the House regime did have some punitive features. The women’s correspondence was subject to examination by the superintendent, in chapel they sat behind a screen which hid them from the view of the rest of the congregation14, and no man, even one of the male Guardians, was ‘to be permitted on any pretence to converse with any of [them] without a written order of the Patroness or Vice-Patroness’.15 In a gesture which emphasized their break with the past, magdalens relinquished their own names on entry, and were assigned a number by which they were known throughout their stay. So Anne Mechland, the first entrant, became ‘Mrs One’, and so on.

On the other hand, there was an acknowledgement that moral reform must be underpinned by social rehabilitation. The aim of the House, as described by the dean of Ardfert in one of his sermons on its behalf, was to equip the penitents to depend for their future livelihood not on ‘the miserable wages of sin, but on the just fruits of industry, honesty and virtue’. For this reason, ‘particular care has been taken to teach them such works and manufactures as may qualify them hereafter to earn a comfortable subsistence’. 16 Training was given in various branches of needlework, inmates were entitled to at least part of the proceeds of the sale of their work, and the magdalen was only discharged when she had been reconciled with her family or had been furnished with a skill with which she could support herself. A typical example was Agnes Dillon, released in 1776, ‘having learned the tambour to perfection in the House … [and] is now enabled to get a decent livelihood’.17

In order to be dismissed regularly from the House, it was necessary for the magdalen to have behaved satisfactorily during her time there, to have shown sufficient evidence of repentance and a determination not to relapse into vice. The usual length of stay was about two years, although this did vary according to circumstances. For instance, Mary Talbot, one of the youngest entrants, remained in the institution for over five years, and during that time was taught to read ‘and to do every kind of work taught in the House’. On the other hand, a few inmates were discharged creditably within a shorter period if they had behaved well and if the authorities were satisfied that suitable provision had been made for them. So Elinor Ward left after eighteen months to go to her uncle ‘in expectation of marriage’, and Honora Mullin, Sarah Newman and Ann Hanway, all of whom had spent only five months in the House, were released in October 1773 in order to join a larger group of former inmates who were emigrating to America.

Those leaving the house regularly were entitled, at Lady Arbella’s discretion, to a bounty, or grant, of three guineas, initially payable in full at the time of departure. This arrangement was soon amended, and thereafter the bounty was paid in instalments rather than in a lump sum, the first to be paid on departure, the balance after a year if proof of good conduct during that time was forthcoming. In 1785 Lady Arbella, finding herself ‘most disagreeably deceived’ by one woman ‘who behaved well till her year was expired … and then relapsed into vice’, extended the probationary period to two years. In addition to the bounty, clothes were supplied to those who needed them, some were also given books – usually a bible and prayer book, and devotional works – while others were provided with the equipment which they would need in order to earn their living outside the House. When Ann Sherwin left in 1779, for example, she was given a tambour, handle needle and scissors, and was later advanced 13s 6d to buy material for her work.