Journal Volume 6 2010

Sir William F. Butler (continued/9)

The Campaign of the Cataracts

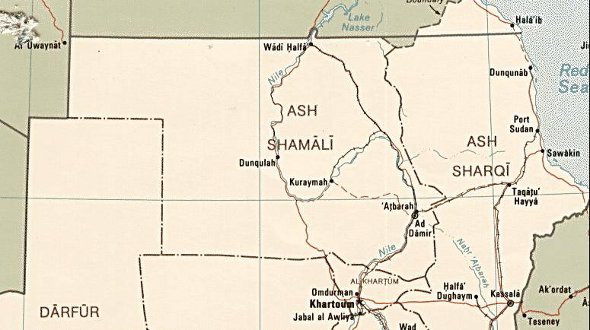

Since the beginning of the 19th century Sudan had been governed by an Egyptian administration. The population was mostly black Africans of the Nubian and Nilotic tribes but dominated by desert nomads called Arabs but in reality a mixed race of Arab and black African blood. Their main trade was slavery in which they seized and sold black Africans from the Nubian and Darfuri regions. The Arabs detested Egyptian control mainly because it interfered with the slave trade.

From the 1870’s a revolt against Egyptian rule had been growing in strength. It was partly political but mainly a jihad led by a Moslem cleric called Muhammad Ahmad who proclaimed himself ‘the Mahdi’: the promised redeemer of Islam. In the summer of 1883 the Egyptian government assembled, at Khartoum, an army of 7,000 Egyptian infantry and 1000 cavalry under a British general, William Hicks, and twelve British officers. They set out to relieve El Obeid a desert town, 700 km northwest of Khartoum which had been captured by the Mahdists. They encountered a Mahdi army of 40,000 and were annihilated.

British public opinion was outraged but the Egyptian government, financially unable to sustain another war, decided to evacuate the Sudan. The main task was to evacuate the Egyptian garrisons scattered across the country. The man selected for this task was Charles Gordon who had already served for two years 1873 - 1874 as Governor during which time he had brought some integrity into the administration and had severely disrupted the slave trade. He was the popular choice of the British press which complained loudly of the blow to national prestige caused by the defeat of Hicks. Mr Gladstone, the Prime Minister, was desperate to avoid any further military entanglements in the area. There were problems enough trying to achieve stability in Egypt. Gordon’s orders were to organize the evacuation of all Egyptian forces from Khartoum and outlying garrisons and leave Sudan to the Mahdists.

When he reached Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon immediately began a series of actions which were at variance with his instructions. Nobody knows why he failed to implement them but nobody was surprised. Although a popular hero in England, he was absolutely the wrong man to implement a strategy devised by the British Government. Never in his life had Gordon carried out orders which varied from his own perception of what needed to be done. The possible reasons for his change of course may include the following:

-

-

The Egyptian garrison in Khartoum may have preferred to mount a fixed defence rather than risk a withdrawal through Territory controlled by the Mahdists

-

Gordon had previously governed the region successfully, creating a reasonably honest administration and curtailing the slave trade and may have hoped his prestige would counteract the charisma of the Mahdi

-

Many commentators have drawn attention to Gordon’s personality: he was very devout Christian, his dearest possession was his Bible and he expected and may have hoped to die a martyr

-

Gordon’s position in Khartoum was strong to begin with. The city was protected on three sides by the Blue and White Niles. He had 7,000 Egyptian soldiers and food and ammunition for six months. He was a Royal Engineer and immediately built fortifications on the open side. However by March the Mahdists had cut the telegraph line to Cairo and deployed 50,000 men around the city ending all hope of a breakout.

As Gordon’s predicament worsened a clamour arose in Britain for a relief expedition. Gladstone held out as long as he could against what he perceived as moral blackmail but eventually the press, his cabinet colleagues and even Queen Victoria prevailed. In August an expedition under Sir Garnet Wolseley was dispatched.

Wolseley and his trusted inner circle of staff officers, including Butler, had already been appraising the situation. Wolseley was the most successful general of the period. He wasn’t liked in the army probably because he was competent and a meticulous planner which always generated mistrust in the British officer corps. However Butler liked and trusted him and looked forward to taking part in a campaign which for the first time he found morally justifiable.

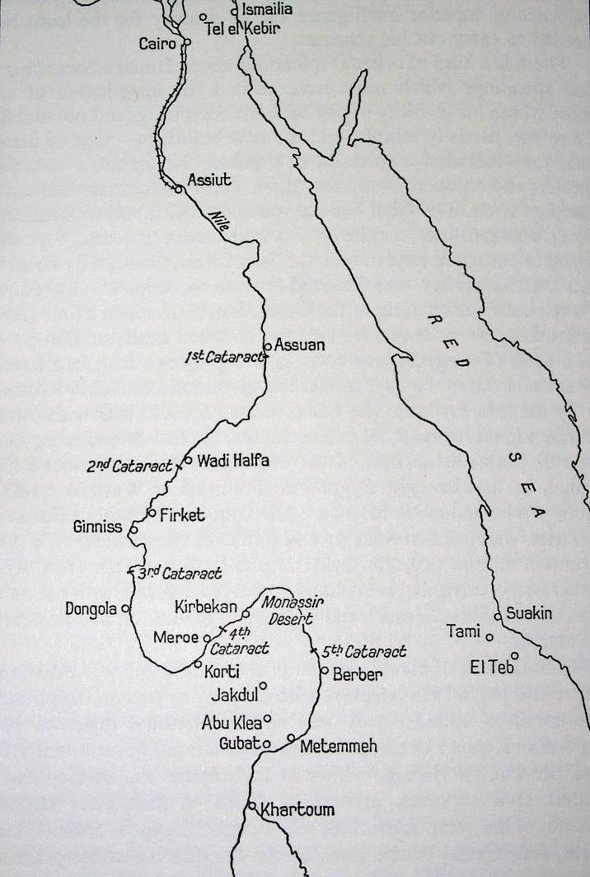

The alternative routes available to Wolseley were either from Suakim on the Red Sea coast overland to Berber on the Nile or up the Nile valley. The Suakim route was rejected because of the long distance over the desert and the fact that 4,000 camels at least would be needed to carry supplies including water. The Nile route eliminated the water problem and offered the hope that river boats would meet part of the supply problem. Butler was put in charge of the project to design, obtain transport and commission on the Nile 400 boats for the expedition. His team included officers who had served on the Red River expedition in 1870.

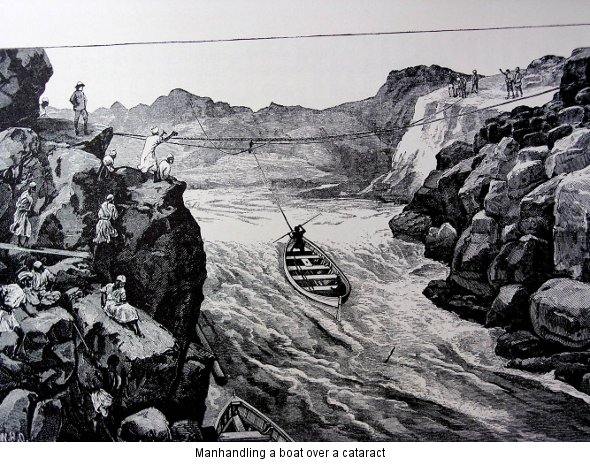

The prototype was built and tested at Portsmouth on 18th August. She was 32 feet long, 7 feet beam and drew 10 inches. She had to be light enough to be manhandled over cataracts, to be capable of moving under sail in deeper water, to carry 4 tons of stores and 10 men. She passed the harbour tests. Then builders had to be found and contracted to build 400 to be ready for shipment to Alexandria by mid September. By a miracle of organization Butler himself was ready and waiting at Alexandria only six weeks later to see the boats unloaded from a steamer.

In parallel with the procurement of the boats Butler arranged for a corps of ‘voyageurs’ to be brought from Canada. There were almost 400 of them including 83 Indians. One of the latter was an old friend of Butler, William Prince, Chief of the Swampy Indian tribe who had crewed his canoe on Lake Winnipeg 14 years earlier.