Journal Volume 4 2004

Lead, Kindly Light? Education and the La Touche Family (continued/2)

Eighteenth Century

While the Penal Laws were still in force, elementary education for poor Protestants was organised and provided by benevolent individuals in some parts of the country. In eighteenth century Dublin there was a climate of growing economic prosperity and a fashion for philanthropy among the rich. There was much effort but mostly little real sympathy for the poorest (i.e. the majority) in society, who were expected to accept their lot just as the rich accepted their pre-eminence.

Charity Schools

An advertisement published on behalf of various philanthropic institutions in 1752 requested support for Charity Schools. Such schools helped children “at present a Nuisance and Burden to their country, to become a Treasure and Blessing to it; that will make honest and industrious men of those who have been bred up in Thievery and Rags ... that will multiply obedient and peaceable Subjects to the King and render the Protestants of Ireland safe in their Lives and Possessions”.

The finances of some of the Charity Schools were looked after by the La Touche Bank, which was considered  safe with its proven financial record. Its senior partner, the banker David II, was an extremely wealthy man, acquiring land in Dublin, Carlow, Leitrim, Kildare, Tipperary and Wicklow. At the time of his death in 1785, his rental income was £25,000 and the bank's profit was £25,000-£30,000. (These figures may be multiplied by 50 to give today's equivalent.) His three sons who survived him: David III (the first Governor of the Bank of Ireland), John and Peter were partners in the Bank. Later, they took in their cousin William Digges La Touche as a Partner, following his distinguished service as Britain's representative in Basra in the Persian Gulf.

safe with its proven financial record. Its senior partner, the banker David II, was an extremely wealthy man, acquiring land in Dublin, Carlow, Leitrim, Kildare, Tipperary and Wicklow. At the time of his death in 1785, his rental income was £25,000 and the bank's profit was £25,000-£30,000. (These figures may be multiplied by 50 to give today's equivalent.) His three sons who survived him: David III (the first Governor of the Bank of Ireland), John and Peter were partners in the Bank. Later, they took in their cousin William Digges La Touche as a Partner, following his distinguished service as Britain's representative in Basra in the Persian Gulf.

The Marine School

David III acted as Treasurer for the Marine (later the Hibernian Marine) School which catered for the orphaned children of seafaring men. It opened at Ringsend in the autumn of 1766 to “lodge, diet, clothe and instruct” up to twenty boys aged seven to ten years. They were to be “apprenticed at thirteen or fourteen or sooner (according to the constitution and fitness of the Boys) to Masters of Ships”. The Opening was attended by the Governors, including three members of the La Touche family, who saw seventeen of “those poor Children's appeerance (sic) in their new Clothing”. The children's mothers, mostly widows, it was reported, were also present. In 1773, the school moved to Sir John Rogerson's Quay, and 2 years later was granted a charter.

Charter Schools

The first Charter Schools had been set up in 1733, targetting the very poor native Irish. It has to be said that the parents who let their children attend these Protestant establishments saw it mainly as an alternative to near starvation. Although the schools were administered officially by the Incorporated Society, the fate of the children depended on individual teachers. Too often children were poorly fed, clothed and housed and received hardly any instruction but were forced to labour in factories or farms attached to the schools. The Methodist minister, John Wesley, described such a school at Ballinrobe as a picture of “slothfulness, nastiness and desolation”. An examination of the general situation found that children in the Hedge Schools were “much forwarder than those of the same age in Charter Schools”, as well as being clean and wholesome.

Charter Schools came under the scrutiny of the Lord Lieutenant in 1788. He appointed commissioners to inquire into the administration of the several funds and revenues for the purpose of education. One Commissioner commented “the State of most of the Schools ... I visited was so deplorable as to disgrace Protestantism”. However, the otherwise damning report found the Hibernian Marine School “which is managed with due economy, highly useful to the public and the funds should be increased to enable as many children as the building will accommodate”. About one hundred and fifty boys were being maintained in 1788, at an average cost of 10s 3/4d a day (£11 9s 6 3/4d yearly).

The King's Hospital

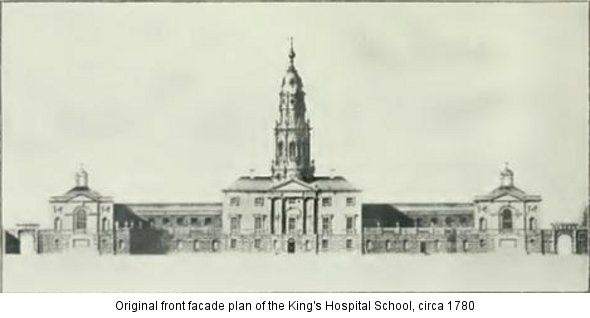

David III was also known to be interested in one of Dublin's oldest schools, the King's Hospital or Blue-coat School and his son John served on the governing committee. Founded in 1670, for the sons of Redeemed Freemen, a competition to design new buildings was held in the 1770s. The winner Thomas Ivory designed the new premises for the school to be located at Blackhall Place. The building is now occupied by the Incorporated Law Society.

David had taken up the reins as head of the La Touche Bank after his father's death in 1785. He and his brothers, John and Peter, had a vast monument erected to David II in Christ Church, Delgany, the village where the reputedly very charitable man had died in his favourite country home, Bellevue.

The year Charter Schools came under scrutiny, 1788, saw the marriage of Peter La Touche to Elizabeth Vicars, a cousin of his first wife Rebecca Vicars who had died two years previously. They chose Bellevue, left to Peter by his father, for their home in the country. There were no children from either marriage. But Elizabeth was a formidable woman who channelled her energies into providing support and schooling, not only for causes that interested her or her husband in Dublin, but also for poor, often orphaned children in Delgany as well.